Since Bell Centennial was designed for such specific purposes, its forms are very unique. Some serve technical purposes that improve reproduction, some deal with legibility issues, and some act as stylistic devices.

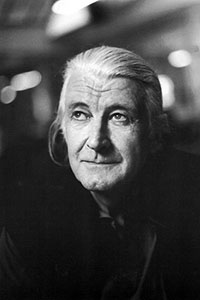

AT&T wanted the new typeface to have more of a modern feel to it; one that would work well with Helvetica (history), the typeface used at the time in the AT&T corporate identity developed by Saul Bass (1920–1996, bio). Though formal changes were made to better match Bell Centennial with Helvetica (i.e., the slanted stroke ends in Bell Gothic became squared), the new face would not simply be an adaptation.

AT&T wanted the new typeface to have more of a modern feel to it; one that would work well with Helvetica (history), the typeface used at the time in the AT&T corporate identity developed by Saul Bass (1920–1996, bio). Though formal changes were made to better match Bell Centennial with Helvetica (i.e., the slanted stroke ends in Bell Gothic became squared), the new face would not simply be an adaptation.

The main problem with Helvetica was that its forms lost some functionality at the small sizes used in the phone book due to its closed letter shapes.

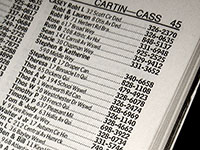

The new typeface, above all else, had to be very legible at small sizes (6 point, to be exact) – especially the numbers; according to Carter, the most valuable aspect of Bell Centennial is allowing for this by using very open forms. To do this, Carter emphasized counter space by using square cut terminals on letters with curved strokes, like in the a, c, e, g, and s. He also increased the white space of the letters by not using horizontal terminals, as well as straightening and shortening curves in characters like g, y, r, e, C, G, J, S, 3, 5, 6, and 9.

The letters were allowed a bit more breathing space as far as letterspacing which prevented characters from bleeding together on the page.

Obviously the numbers of Bell Centennial played a crucial role, so Carter made sure to create a clear distinction between numbers with similar forms like 5 and 6, or 3 and 8.

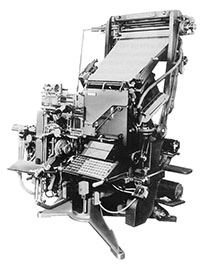

Maybe the most unique of Bell Centennial's forms are in place to solve problems during production. Since the phonebook is printed at high speeds and on low-quality paper, the ink has a tendency to spread out on the paper (this effect is called “dot gain”). Since the slightest spread greatly effects the shape of such small letterforms, Carter incorporated notches (called “ink traps”) at the corners for compensation.

Maybe the most unique of Bell Centennial's forms are in place to solve problems during production. Since the phonebook is printed at high speeds and on low-quality paper, the ink has a tendency to spread out on the paper (this effect is called “dot gain”). Since the slightest spread greatly effects the shape of such small letterforms, Carter incorporated notches (called “ink traps”) at the corners for compensation.

Bell Centennial introduced two new weights to the phonebook, allowing more depth in hierarchy and opportunities to highlight special listings.

Predicting that advertisers would pay extra money for increased visibility, a Bold Listing weight was developed. It did not have lowercase characters and had an exaggerated capital height – sitting below the baseline and utilizing the space normally used by lowercase descenders. An alternate version was also developed to sit on a standard baseline. [note: it appears as though the alternate version of Bold Listing has been abandoned in the OpenType version of Bell Centennial; instead, the Bold Listing weight now sits on the standard baseline by default.]

It was apparent in test settings that Bold Listing required a companion font – one that was somewhere in between Address and Name & Number. Sub-Caption was developed, and proved helpful in giving additional information about advertisers or in listing entries for large institutions with multiple departments and numbers.